Fabian Cancellara keeps his three in special niches built into his home sauna. Tom Boonen has an elegant four-storey shelving space in his home for his.

But Sean Kelly keeps his two cobblestones from Paris-Roubaix, along with the rest of his trophies and jerseys from his career, out the back.

“They are all at the rear of the house. Just in a room out of the way,” he says.

Yet out of the vast collection of silverware — from the two enormous cups awarded in Sanremo to the swirling statuettes of the Giro di Lombardia — and the dozens of yellow, white and green jerseys that Kelly proudly displayed at the Rouleur Classic in London, those unassuming, dull grey lumps of rock remain on a higher plane.

“Of course the Roubaix stones are always ones that you remember pretty clearly,” Kelly says.

“The ‘84 one, my first Roubaix, that’s the one I remember very clearly. Because of Paris-Roubaix and the way I was riding — I felt I could win the race from a long way out — that’s the one I have great memories of.”

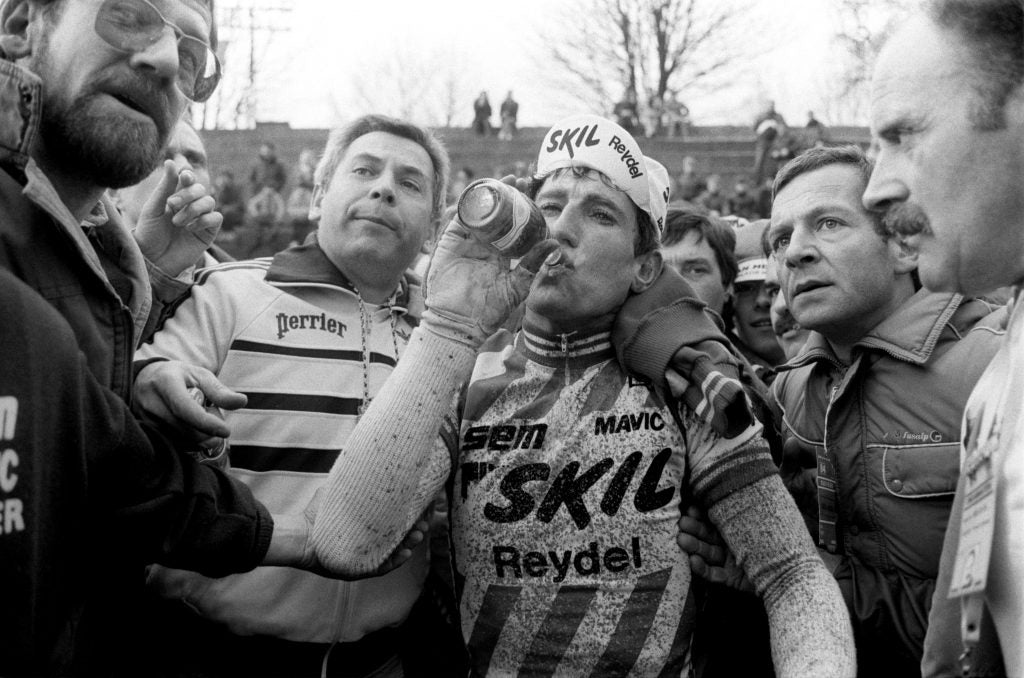

Kelly recounts with remarkable detail the final throws of the dice in that year’s race, a sodden slog through the mud that took Kelly, then 27 and in a career purple patch, over seven and a half hours to complete.

Alan Bondue and Gregor Braun were up the road while Kelly, itching to attack with over two hours remaining, was told to keep calm by his director sportif at Skil, Jean de Gribaldy.

With 40km to go, he and the Belgian Rudy Rogiers made their move and passed the leaders 15km later. The pair entered the velodrome together and Kelly, the better sprinter, dispatched his rival with ease.

“I was confident that if we could get to the final 200m I could win a sprint, but you’re always concerned that something would break on the bike, on that sort of terrain, you could get a blowout any time.

“The feeling when you get onto the track in Roubaix of course, it is a great feeling. All the difficult stuff, the dangerous stuff, is over. And to get through the race and onto the track in a position to be going for the victory… and to have a great chance of going for it, I was in a real good position that year.”

Today, over 32 years on from that spring Sunday in 1984, it’s obvious that Kelly still gets a thrill from holding the asymmetric lump of granite, haphazardly mounted onto a scruffy stone plinth.

He grins as he contemplates the rough edges, and lets out a mock winners’ roar as he hoists it up to shoulder height as he did in 1984.

“I had to use two hands…” he reflects. “Cancellara might have done it with one.”

There is no sweeter feeling than the exhausted lactic burn in your triceps as you take delivery of the most famous prize in cycling on the top stem of the podium on the grass in the Velodrome de Roubaix.

And, judging by the expressions of the men on the lower steps ever year, no lesser podium place is more bitter.

“You have to go so deep in Roubaix, it is such a long difficult race, when you arrive like that with a group of three riders, four riders, and you finish second or third, it is…. it’s a great place to be but it’s a disappointment when you see guys finishing in front of you,” Kelly says.

“There, more than anywhere, the winner takes it all.”